Lifetracing 2. The Advent of the Engines

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Previous: Lifetracing 1 | Next: Lifetracing 3

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 This section will explain the way in which identity construction and performance have changed with the advent of search engines. Social software has become increasingly entangled in relations with search engines, creating software-engine relations, which have major implications for the construction and performance of identity online. It will also explain how the idea of “identity placement” has changed and how search engines endorse the claimed identity.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The rise of search engines took place about the same time as the rise of blog software. When we blog we feed our blog database with content but we also feed the databases of the engines. Once a blog post has been published on the web it becomes part of “a vast and recursive network of software agents, where it is crawled, indexed, mined, scraped, republished, and propagated throughout the Web” (Rose 2007). Blog posts automatically become part of this vast network because of standard features in the blog software which connect the blog to other blogs (through trackback and pingback) but also to engines (through RSS and ping). When the blog as a platform for identity performance is automatically indexed by search engines it can be argued that the identity construction in the blogosphere is largely performed by the engines.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Illustration 3: Google Me Business Card by Ji Lee

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 2.1 Search Engine Reputation Management

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Google — the number one search engine and website — is for many people the main entry point to the web (Dodge 2007). As such it also acts as an identity constructor and manager that reveals the traces you leave online and the traces others have left about you. Search engines are often used to find people either for business or personal purposes [3] and in an era in which “You’re a Nobody Unless Your Name Googles Well”, it is important to boost your visibility in search engines (Delaney 2007). While you can have a certain amount of control over what you write, post and upload it is hard to control what others write, post and upload about you. This has led to the practice of online identity management which is largely performed through search engines.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 The euphemistic phrase “reputation management issue” describes what happens when you have a problem arise in search engine result pages. Whether it’s the result of an algorithm change, bloggers, or social media sites jumping on negative news or other negative linking bandwagons, reputation management issues are a major pain for brands. (Bowman 2008)

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Search Engine Reputation Management (SERM) tactics are often used by brands to disguise negative search engine results in order to protect their brands. A recent example of creating a search engine friendly identity using SERM techniques is the case of Nina Brink. Brink was involved in a scandal surrounding the initial public offering of internet service provider World Online in 2000. In 2009 a search for her name in Google still returned two negative results related to the scandal in the search engine’s top ten. In order to clear her name she is said to have hired a SERM specialist to improve the ranking of the positive results in order to drop the negative results out of the top ten [4]. When you now search for Nina Brink on Google the second result reads “Nina Brink is also a loving mother” (see illustration 4). This seemingly odd result raises the suspicion of SERM tactics being used to influence the results.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Illustration 4: Nina Brink Google results.

Result nr. 2: “Nina Brink is ook een liefdevolle moeder” means “Nina Brink is also a loving mother”

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 As employers can ‘Google’ their employees and potential job candidates (Cheng 2007) it is important to be able to have a sense of control over the search engine results of your name. Chances are that people are very willing to submit a large amount of information about themselves to search engines in exchange for a sense of control over the outcome. This will be further addressed in paragraph 4.1.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 2.2 Indexing and Privacy Issues

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Users need to be aware of the fact that search engines have an indexing fetish: they want to index as much information as possible, not in order to create a “complete” index but to have as much user data (which can be sold) as possible:

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Google suffers from data obesity and is indifferent to calls for careful preservation. It would be naive to demand cultural awareness. The prime objective of this cynical enterprise is to monitor user behaviour in order to sell traffic data and profiles to interested third parties. (Lovink 2008)

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Software facilitates the indexing by search engines through the establishment of software-engine relations and the use of standards. For example, blog software automatically notifies the network (including the search engines) of a new blog post and Google Blog Search indexes anything that publishes an RSS feed. This means that Google Blog Search not only contains blog posts but also public status updates from the micro-blogging and social networking service Twitter. If you have a public profile, every single tweet (Twitter status update) you post on Twitter will be indexed by Google. Single tweets appear in Google and can be taken out of context. This is the main reason why some users have a private Twitter account: it cannot not be indexed by the engines.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Social networking sites are favorite targets for search engines as they contain user profiles filled with data and a large amount of user-generated content. The indexing fixation of the engines is slowly permeating the walled garden structure often seen in social networking sites. Walled gardens are closed environments which require a registration and login to enter. Once inside it feels like a safe haven and the walled gardens usually do not allow indexing. This structure in social networking sites also prevents anyone, who is not logged in to the network and who is not your friend, from seeing your profile. Facebook used to be the prime example of a walled garden social networking site: what happens on Facebook stays on Facebook. However, social networking sites are increasingly working together with search engines to allow the indexing of their members’ profiles.[5]

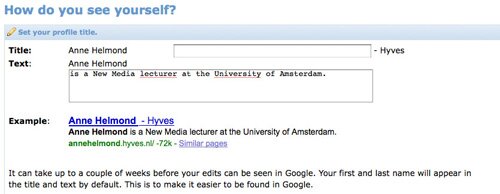

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 On January 30, 2009 the Dutch social networking site Hyves opened up its walls and allowed Google in to index profiles and link them to surnames in Google. This decision, which was not officially announced to its 8.6 million members is based on an opt-out option. If you do not want your profile indexed by search engines you should opt-out. However, by default your last name is visible in Hyves so by default you will be indexed by Google. Indexed individual data records are now public by default. In return Hyves offers its users a sense of control by allowing customization of the search engine results for their profiles.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 The social web has seen the advent of a new type of search engine focusing on people search. Wink, yoName, Spock and Pipl are search engines specialized in finding people. By entering a name, username or e-mail address it not only searches the web but also the social networking sites and online communities like MySpace, LinkedIn, Friendster, Digg, YouTube, etc. Your digital traces online have now become increasingly indexed by search engines.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 The following section will describe how these digital traces are produced by the conscious and unconscious recording of our daily lives and how software has given rise to the phenomenon of lifelogging and the related self-surveillance and statistics envy.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

Illustration 5: Customizing Google/Hyves results.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Footnotes

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 [3] Figures range from “7% of all searches are for a person’s name, estimates search engine Ask.com” (Delaney, 2007) to “Singh says around 30% of searches are people-related” to “Tanne says 2 billion searches per month are on people (Facebook data tends to suggest this is probably vastly underestimated).” (Arrington, 2007)

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 [4] Two Nina Brink websites: NinaBrink.com and NinaBrink.info are registered by an employee of UniversalXS, a company specialized in Search Engine Optimization and Search Engine Reputation Management (Deiters, 2009).

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 [5] Private accounts on social networking sites are a common way to prevent indexing by search engines. The walls of Facebook are solid and personal and potentially privacysensitive data cannot ‘leak’ out of the garden when your profile is set to private. Different privacy levels also control the flow of data within the walls of the walled garden and determines who may see what.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Previous: Lifetracing 1 | Next: Lifetracing 3

Comments

Table of Contents

Activity